A full guide to vape aerosols, formation, properties and comparisons: Post 3.

Overheating and beyond

Summary

This is the third Substack post of a series of posts describing vaping aerosols, their properties, their optimal regime of operation and comparisons with tobacco smoke and other aerosols. Understanding how vape aerosols form, operate and can be tested provides the knowledge to understand their pleasurable usage, their toxicity profile and relative safety with respect to tobacco smoke and other aerosols and pollutants. Without being “experts” this knowledge reassures our confidence on the role of vapes in harm reduction and serves us to counter ignorant and malicious disinformation.

This knowledge (which I try to present accessibly) reassures our confidence on the role of vapes in harm reduction and serves us to counter ignorant and malicious disinformation.

Previous posts: Post 1, Post 2.

Post 3:

I described in Post 2 the Optimal Regime of vaping in terms of thermal physics as a an energy exchange trade-off that can be tested in the laboratory in terms of functional curves that relate supplied power W with the mass of e-liquid vaporized MEV.

In this post I explain what happens when a vape device is operated or tested in the laboratory in the Overheating Regime at power levels above the Optimal Regime, hence at coil temperatures above e-liquid boiling temperatures. I explain the thermal processes taking place under this regime, modifying the boiling process, leading to an exponential rise in toxic byproducts and to a critical end point known as a “dry puff”. These are complicated and unstable processes whose full details are still not completely understood.

What can go wrong under the Overheating Regime

Overheating Regime when puffing with supplied power above the Optimal Regime is characterized by much more energetic and unstable thermal processes that significantly modify the cyclical balance of heat exchange of the boiling process, increasing the residual heat and modifying the chemical composition of the aerosol. Users perceive these changes, since puffing a device under these conditions is no long sensory pleasant.

Nucleated boiling.

As coil temperature go above e-liquid boiling temperature, boiling continues but becomes more energetic and unsteady than normal boiling discusses in previous posts, following these two regimes: nucleated boiling and film boiling. Similar type of boiling regimes occur in other thermal systems where a heating element, typically a coil, heats a liquid: electric boilers, kettles and nuclear reactors.

Pool boiling describes a thermal system in which the metallic heating element (a coil) is completely immersed in a liquid within a closed insulated container. It is the simplest analogy to illustrate what might happen in a vape device. The evolution from normal to nucleated to film boiling is theoretically described by the Nukiyama curve (Figure 1), plotting supplied heat flux q = Heat/(area X time) = Power/area as a function of Tc-Tb, the difference between coil and boiling the temperatures:

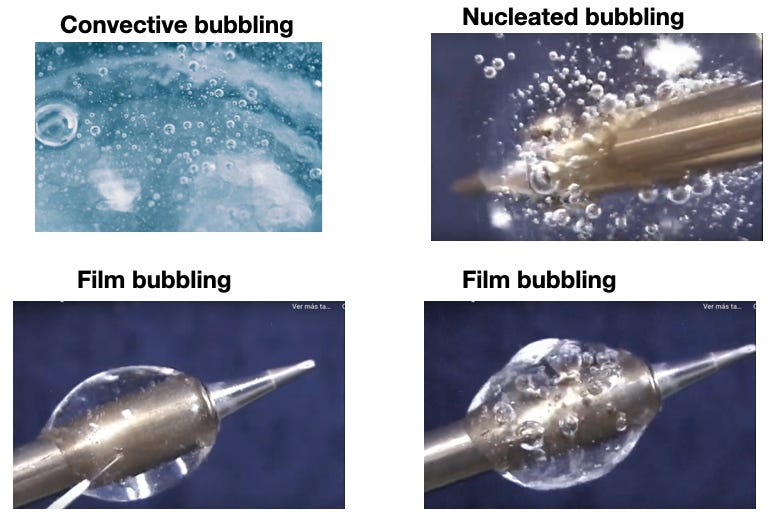

To the left of point A we have Normal Boiling described in Post 1 and Post 2: initially small air bubbles form and move under simple convection circular patterns, absorbing vapor and clustering in the liquid surface where they burst and release vapor. Nucleate Boiling (from A to B) initiates by supplying a sequence of fixed small amounts of extra heat (extra power on the coil) in a series of steps. After supplied heat by a number of increasing steps the bubbles become more numerous, larger and mobile, flowing throughout the bulk liquid along very complicated convection patterns. This is shown schematically in Figure 2 and with photographs in Figure 3

Bubbles absorb heat and fill with more vapor from the liquid mixed with air, increasing their internal pressure to balance the liquid pressure, becoming sufficiently stable to collide, merge and cluster (nucleate) gradually into larger bubbles around the heating element. However, contrary to what we would expect, the extra heat supplied to the coil in nucleated boiling does not cause a proportional increase of vapor with respect to normal boiling (as it happens in the Optimal Regime). I explain the reasons below.

The vaporization latent heat is the quantity of heat that needs to be absorbed at constant boiling temperature to vaporize a given liquid mass. It slowly decreases as temperature and pressure increase, becoming zero only under an extreme condition known as the “critical point” (typically at extremely high pressures). For thermal systems close to atmospheric pressure the latent vaporization heat remains roughly constant, so the extra supplied heat does not contribute to a significant proportional increase of vapor mass. However, vaporization proceeds and the liquid levels decrease.

Microscopically, the amount of produced vapor is directly dependent on the proportion of liquid molecules that escape from the liquid surface to the gas area once their kinetic energy (motion energy) surpasses the binding energy of intermolecular forces that keep them bound in the liquid. Since temperature is the average of molecular kinetic energy, this molecular escape follows from a sufficient increase of temperature from extra supplied heat that is absorbed for vaporization.

However, when the escaped molecules are in excess in the gas area, they loose energy by colliding and falling back to the liquid (the vapor condenses). Therefore, the heat surplus of nucleated boiling does not generate significantly more vapor in proportion to the extra supplied heat to the coil. Rather, the increase of coil temperature produces more molecular kinetic energy, which is compensated by more collisions (more condensation). The liquid decrease at same levels as in the Optimal Regime but do so more rapidly in each step.

As more power (heat) is supplied coil temperature increases and residual heat accumulates. Depending on the chemical properties of the liquid, at each step of supplied heat chemical reactions in the gas area that were dormant in coil temperatures below the boiling point might become active and energetic, producing more byproducts at higher concentrations. The same happens in a vape device.

Critical Heat Flux towards Film boiling

As steps go on supplying power to the heating element (from B to P) its temperature further increases, bubbles continue growing and merging, ending up covering a significant part of the heating element and most of the liquid-gas surface, absorbing more heat. As the process goes on (from P to C) supplying more power and rapidly increasing Tc, a maximal value of heat flux is reached, known as Critical Heat Flux (CHF) where the Nukiyama curve of Figure 1 reaches a maximum and heat flux begins decreasing from C to D, even if the temperature keeps Tc-Tb increasing. This occurs because the bubbles now cover a sufficiently large part of the heating element to form a film that partially insulates it from the liquid, retaining inside the film sufficient heat to counter the supplied heat flux. This is the transition to film boiling.

The point D, where the Nukiyama curve has a minimum known as the Leidenfrost point, is characterized by a full clustering of the bubbles to form a film that fully covers the heating element, isolating it from the liquid and retaining all heat supplied to the coil, further increasing dramatically its temperature. However, It is important to stress that it is very difficult to verify experimentally the theoretical Nukiyama curve of Figure 1 beyond the CHF into the Leidenfrost point towards film boiling, since the expansion of the film to cover the coil is an extremely unstable process at very high temperatures, with liquid becoming depleted to levels in which the heating element is no longer totally immersed, destabilizing and collapsing the film with the heating element emitting all its retained energy by radiation at temperatures that may reach above 1000 °C. At this critical point wires might melt and most physical structures malfunction and break down (something that might occur already at the CHF).

What about vapes?

There are similarities between Pool Boiling and vapes, both involve a metallic heating element and boiling liquids. The following are two basic important differences:

In Pool Boiling the step by step heat supply might be absorbed by vapor evacuation through forced convection to extract it (for example) for heating water for bathing, though nobody is inhaling it. In vaping the step by step process is a puff cycle, so at each step the supplied heat is almost simultaneously absorbed to vaporize e-liquid but also by forced convection through inhalation.

In vaping, the heating element (coil) is exposed to air (through the inhalation conduct) even if totally immersed in the e-liquid. Decreasing liquid levels increase air exposure of the coil, which complicates the thermal variables of the boiling process.

However, the most important difference is in the heating element (coil). In vaping it is not a simple metallic coil, but a complicated structure with metal wires coiling around organic biomass (the cotton wick), both in contact with air in the inhalation conduct (see Figure 4 below). As a consequence of this complexity, the heat exchange between the wires, the e-liquid and air exhibits a very complicated dependence on the wire properties and the geometry of the coil/wick.

Two physical properties are essential to understand heat exchange in vape devices:

Capillarity: the capacity of liquid layers to rise along the wick fibers

Wettability: the capacity of liquids to extend and cover solid surfaces. This property in metallic surfaces (wires) is very different from porous surfaces (wick fibers)

The action of these two properties widely varies with different designs of vape devices making it difficult to fully understand thermal effects under overheating conditions.

Vaping under an Overheating Regime above boiling temperatures (188-288 °C) can also be represented by the Nucleated Boiling part of a Nukiyama curve up to CHF (from A to C in Figure 1). However, since operating vape devices involve puff cycles of supplied and absorbed heat (Power = heat/time), the functional curves introduced in Post 2 plotting the mass of e-liquid vaporized (MEV) vs power provide a better representation of overheating conditions.

As in pool boiling, liquid vaporization remains nearly stagnant (Figure 5) with residual heat accumulating at each step of supplied heat. At temperatures above 300°C bubbles become larger and more energetic, clustering around the coil (see Figure 3). Liquid levels rapidly decrease after each puff, since the extra residual heat increases bulk liquid temperatures, decreasing its viscosity and favoring liquid capillarity and wettability. As more power is supplied in extra puffs, the bubbles coalesce to form insulating films that partly cover the wires in the coil and retain heat, further increasing coil temperature until reaching CHF at roughly 400-450 °C. This is the transition from nucleated boiling into film boiling whose endpoint is a “dry puff”, a different evolution from Pool Boiling as I explain further ahead.

Exponential growth of toxic byproducts.

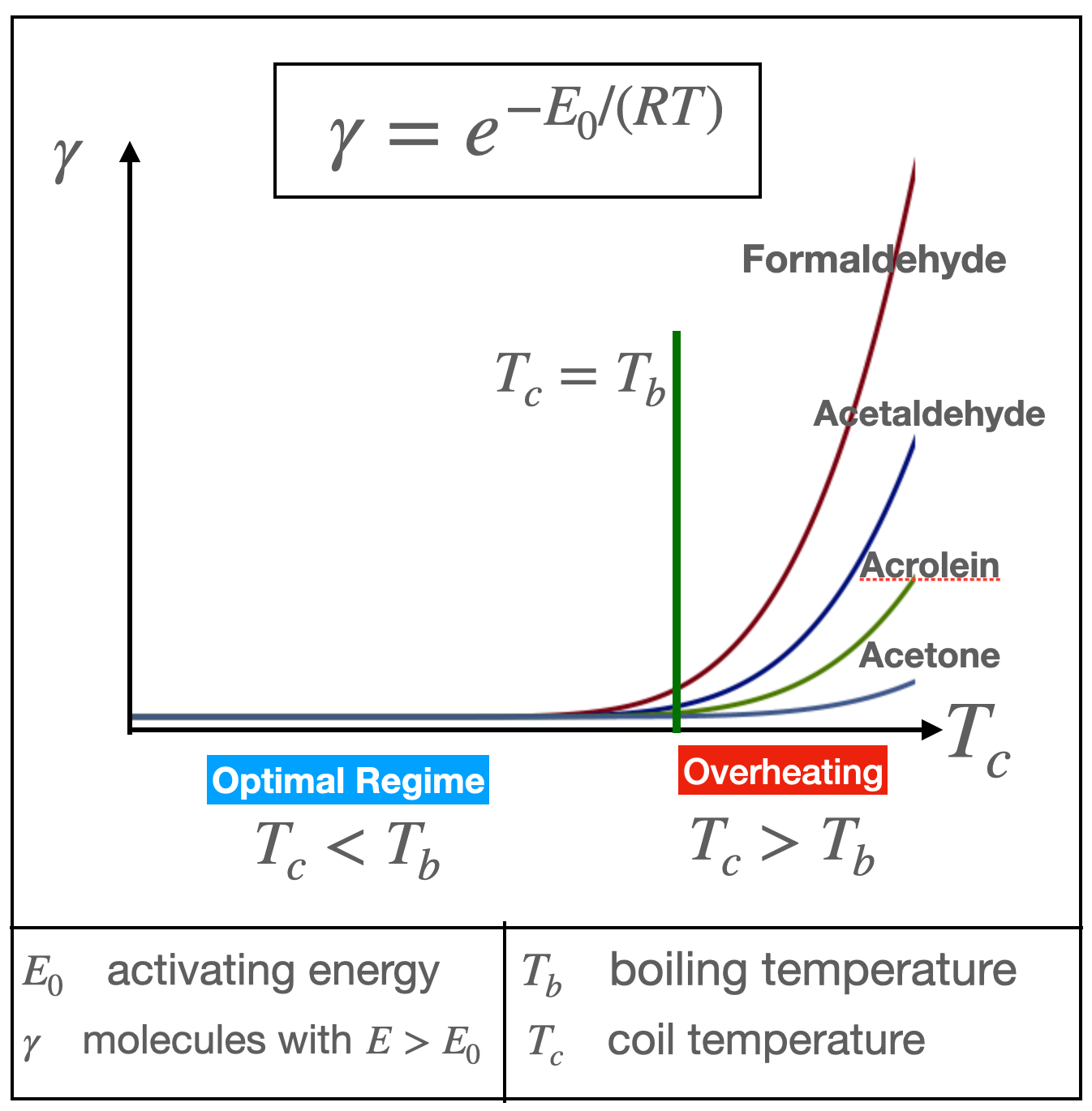

Thermal degradation reactions (low energy pyrolysis) when vaporizing a liquid can also occur in the gaseous region of a Pool Boiling scenario, but in vape devices it has important safety implications. The rate of these reactions in the gas depends exponentially on the temperature and on an activating energy E0 that varies with each reaction (Arrhenius law). This dependence can be illustrated schematically by figure 6 below

The reaction rate (gamma) is the proportion of molecules with energy E above the activation energy E0, which is a different rate for different reactions (different byproducts). Under the Optimal Regime vaporization takes place at roughly constant boiling temperature Tb, which roughly coincides with the coil temperature Tc (locally around the wick). At this temperature (and below) the reaction rate gamma is very small (the left hand side of the exponential curve in Figure 6 with almost zero growth), hence the reactions are weak and produce minute amounts of byproducts, though typically larger amounts of formaldehyde. Operating a device within the range of power defined by the Optimal Regime will vaporize the liquid around the wick at boiling temperature Tb and the reaction rates remain very small .

However, as coil temperature exceeds boiling e-liquid temperature the reaction rates grow exponentially (as shown schematically in Figure 6). This transition between negligible to minute levels to an exponential increase of aldehyde yields occurs also at the supplied power W that marks the passage from the Optimal to the Overheating regime. This is the maximal power allowing for reactions taking place at roughly same boiling and coil temperature. These effects can be seen in the laboratory

The blue rectangles in Figure 7 show the power ranges of the Optimal Regime, while colored dots mark the production yield of the 3 main aldehydes (formaldehyde, acetaldehyde and acrolein). Notice how aldehyde yields are very small within the power ranges of the Optimal Regime, but their production triggers exponentially in the Overheating Regime (just as in the Arrhenius law in Figure 6). As coil temperature increase (300-350 °C) into nucleated boiling, thermal degradation reactions become more energetic (more energetic pyrolysis) dramatically increasing the production of more byproducts in larger yields.

Vapers do not perceive the bubbling intensity, but do perceive a hotter aerosol as increasing residual heat rises the temperatures of the air/vapor mix inside the atomizer, its walls and the mouthpiece. They also perceive the rapid increase of byproducts as a taste deterioration, even without e-liquid depletion (“dry puff”).

However, users specially perceive a clear and more marked taste deterioration from the byproducts of pyrolytic reactions of the cellulose in the wick (specially furans), characterized by a bitter almond-like taste and smell. As shown in the following photographs (not an experiment, but a qualitative evaluation), the onset and advance of pyrolysis as temperature increases of the wick can be easily appreciated visually:

Toasting bread is a useful analogy to understand pyrolysis (and combustion as its end point). A mild power level applied to the toaster produces a light brown tasty bread loaf (low energy pyrolysis). Increasing the supplied power leads to darker loafs that (up to a certain level of power) are still edible (still low energy pyrolysis). Practically all consumers will eat toasted bread at this level or below, since above this power level the loaf comes out dark brown and is no longer pleasant to eat. Increasing the supply of power will further degrade its taste making the loaf repellent and uneatable (energetic pyrolysis). Further increase of power will ignite and burn the loaf (combustion). Applied to vaping: puffing a vape device under overheating conditions is as unpleasant as eating an over-toasted foul tasting loaf of bread and the dry puff is the burnt loaf.

From nucleated to film boiling and the dry puff.

The transition from Nucleate to Film Boiling in vaping is different from Pool Boiling, since the liquid is in contact with a complicated heating element: a wire coiling around a cotton wick (see Figure 4). The films along the wires conduct heat, while the air in the inhalation conduct forms extra bubbles with air and vapor inside the wick (which is already pyrolyzed, see Figure 8) whose pressure increases above the pressure of the remaining liquid. Since heat is not entirely retained by the films covering the wires, there is no Leidenfrost point (“C” in Figure 1). Instead, at the CHF films and bubbles in the wires and wick rapidly collapse, releasing energy into the air as the liquid finally depletes, with the wire transferring heat through radiation almost instantly at temperatures up to 1000°C. This is the “dry puff”.

The “dry puff” is the critical end point of the Overheating Regime. It is not an isolated event in which “puffing was fine” until, suddenly, disaster happened when the e-liquid depletes. However, the overheating process leading to a “dry puff” occurred in an abrupt manner (perceived as instantaneous) in early vaping devices that operated at low power levels (below 5 W) and lacked power or voltage control. It was easy for users to accidentally puff without noticing the rapid depletion of the liquid.

Newer second and third generation devices operated in wider ranges of power and allowed users to control power/voltage and even airflow. This made it much easier for to avid dry puffs and to feel a hot aerosol and/or the degradation of taste at the onset of the overheating regime, even before the completely repellent sensation when liquid depleted. In high powered devices, the Overheating Regime is much more gradual, since these devices can operate optimally in much wider power ranges.

Vaping machines can continue operating through the full Overheating Regime, even into a dry puff, but users discontinue vaping because they perceive a hot aerosol and/or taste/smell deterioration, either abruptly or gradually from the the thermal processes and changes of the chemistry of the aerosol discussed in this post. All this is important to bear this in mind when testing the devices in the laboratory.

What’s next? Prelude to Post 4

We now know how the Optimal Regime for pleasant vaping can be understood and tested experimentally, we also know what can happen under overheating conditions that are also testable in the laboratory. In the next post I will summarize how the aerosol of vape devices is analyzed in the scientific literature. We can see that studies reporting excess of toxic byproducts (above safety markers) can always be traced to various methodological flaws, including testing the devices under overheating conditions.